by Dr. Raul Necochea & Dr. Adam Gilbertson, Dept. of Social Medicine, UNC School of Medicine

Cure research has long raised and troubled the expectations of people afflicted by infectious diseases. Prior to the 1940s, Hansen’s disease (leprosy) was an incurable and severely stigmatizing disease. The Carville Leprosarium was established in 1894, just outside of Baton Rouge, LA, to confine and segregate these patients. In 1921, the US Public Health Service took over its administration and turned it into the only research and treatment facility for Hansen’s disease in the continental US. Since 1901, chaulmoogra oil and its derivatives had been the only available therapies, despite their general ineffectiveness. The same could be said about other treatments used, such

as diphtheria toxoid and heat therapy. For most of the people in Carville, the expectation was a long confinement that severed their ties to their communities of origin and forced the establishment of new social networks, while suffering from a self-limiting illness.

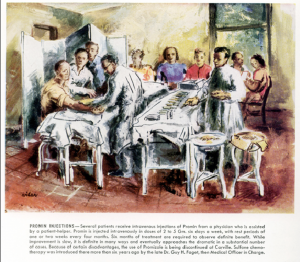

In 1941, Medical Officer in Charge Dr. Guy Faget introduced one more therapeutic: Promin, a sulfone manufactured by Parke Davis. Patients, as before, were eager to try the drug. Following a series of experiments, Carville clinicians managed to limit the drug’s toxicity and enhance its effectiveness. By 1948, chaulmoogra oil had been replaced with sulfone therapy, and scores of patients began to be discharged as “arrested cases”: those with negative bacteriological tests who were deemed unlikely to transmit the disease to others.

How did this cure milestone look from the perspective of patients? In June 2016, we traveled to Carville to find out. Now a State National Guard base, Carville still maintains the buildings where patients lived and, on occasion, it houses Hansen’s patients who travel to Baton Rouge to receive outpatient care. At the Carville archive we consulted clinical reports, daily life records, and correspondence between medical personnel, patients, and family members.

Our research raises questions about what “curing” means to people on the receiving end of novel treatments. How did they approach Promin, considering the long history of ineffective therapeutics at Carville? How did they react to the early

realization that, despite its effectiveness, sulfone treatment was bound to be long and painful? Even after discharge as “arrested cases”,

how would former Carville residents cope with irreversible disabilities and disfigurement? How did they make sense of relapses? How did they re-establish the communal ties they severed under confinement? Patients’ perspectives on cure complement biomedical explanations of its significance.

The experiences of patients who underwent sulfone therapy for Hansen’s disease in the 1940s underscore three points about contemporary HIV/AIDS cure research: (1) patient activism to drive out stigma sustains interest in experimental volunteering, despite previous experiences with ineffective medical and folk remedies; (2) making sense of their response to treatment, patients challenge medical definitions of success against illness, using their own idiosyncratic experiences; and (3) positive identities and networks formed as sufferers of an illness may remain valuable to former patients long past the end of treatment. In coming months, we plan to use the data we collected at Carville to address these and other issues that are pertinent to current efforts to cure HIV, as well as the eventual discovery, and rollout, of a cure.

2 Responses to “Leprosy Cures and Patients’ Expectations”

Anonymous

What a fascinating story. Thanks to Dr. Gilbertson and Necochea for posting this.

Liz Kelly

Thank you!