October 5, 2015 was a remarkable day in the history of science in China. That day, a female Chinese researcher, Youyou Tu, was announced as one of the winners for the 2015 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of artemisinin inspired by traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)[1]. Before winning the Nobel Prize, Tu was awarded the Lasker Awards in 2011 for the same discovery[2]. Tu’s winning of the Nobel Prize is particularly remarkable in that:

- She is the first Chinese citizen who won the Nobel Prize in science and who currently resides in China;

- She does not have a doctoral degree and has no foreign learning or training experiences and she has not published any academic papers in English;

- Her major discovery of artemisinin was done in the 1970s, right in the middle of the Cultural Revolution and the whole project (Project 523) was to answer Chairman Mao’s call to find a cure for malaria so as “to help the North Vietnamese in their jungle war against the Americans”[3];

- And we can keep counting…

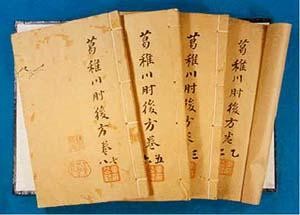

Tu’s discovery of artemisinin was inspired by an ancient TCM medical book, Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang (肘后备急方), as shown in the picture, which was written by Hong GE (last name) about 1600 years ago. Hong GE suggested squeeze the juice out of raw qinghao (called Artemisia annua, or sweet wormwood in English) and then drink it to treat malaria-like symptoms. His method was highly unconventional in TCM, as the tradition was to boil the herbs and then drink the liquid. Inspired by this line, Tu designed a modern scientific way to extract the useful element inside qinghao, which was named Artemisinin afterwards. A major debate around Tu’s discovery of artemisinin is whether it was the contribution based on the philosophy of TCM or just the medicinal herb itself. The same debate is also haunting the TCM approach in the current HIV cure research. Some scientists are using the herbs in TCM to activate the reservoir and then using HARRT to eliminate the virus. Did they choose the herbs based on TCM theory or did they just screen the herbs in TCM randomly? Does this question even matter?

With all these questions unanswered, Tu’s winning of the Nobel Prize will undoubtedly encourage researchers to look for an HIV cure in TCM. But we need to bear in mind the context of Tu’s historical discovery. It was under Chairman Mao’s call and the massive mobilization of all the manpower and national resources. So far, HIV cure research has not yet reached that kind of attention. It is very unlikely that the same mass mobilization can be repeated for HIV cure research, no matter if in China or other part of the world. The road to an affordable and acceptable HIV cure is bumpy, but as long as scientists across all settings keep trying, there is hope.

For more information on the history of TCM, please refer to my earlier blog:

http://searchiv.web.unc.edu/2015/01/23/traditional-chinese-medicine-hiv-cure/

References:

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/06/science/william-c-campbell-satoshi-omura-youyou-tu-nobel-prize-physiology-medicine.html

[2] http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/13/health/13lasker.html

[3] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/17/health/for-intrigue-malaria-drug-artemisinin-gets-the-prize.html

Photo obtained from here

One Response to “A TCM cure for malaria, a Nobel Prize, and an HIV cure”

Diphoko Samane Cornelius

i will much more than happy if we can get an HIV cure & corona